Running Shoes: At Stanford University, California, two sales representatives from Nike were watching the athletics team train. Part of their job was to gather feedback from the company’s sponsored runners about which shoes they preferred. Unfortunately, it was proving difficult that day as the runners all seemed to prefer…nothing.

“Didn’t we send you enough shoes?” the reps asked head coach Vin Lananna. They had – her was just refusing to use them. “I can’t prove this,” the well-respected coach told them. “But I believe that when my runners train barefoot they run faster and suffer fewer injuries.”

Nike sponsored the Stanford team as they were the best of the very best. Needless to say, the reps were a little disturbed to hear that Lananna felt the best shoes they had to offer were not as good as no shoes at all.

When I was told this anecdote, it came as no surprise. I’d spend years struggling with a variety of running-related injuries, each time trading up to more expensive shoes, which seemed to make no difference. I’d lost count of the amount of money I’d handed over at shops.”

I wasn’t on my own. Every year, 65 to 80% of all runners suffer an injury. But why? How come Roger Bannister, who in 1954 became the first man to run a four-minute mile, could change out of his Oxford lab everyday, pound around a hard cinder track in thin leather slippers, not only getting faster but never getting hurt, and set a record before lunch? Then there’s the Tarahumara tribe, the best long-distance runners in the world. These people live in basic conditions in Mexico, in caves without running water, and run with only strips of old tyre or leather thongs strapped to the bottom of their feet. They are virtually barefoot.

Come race day, the Tarahumara don’t train. They don’t stretch or warm up. They just stroll to the starting line, and then go for it, sometimes covering over 200km, non-stop. For the fun of it. One of them recently came first in a prestigious 160km race wearing a toga and sandals. He was 57 years old.

Unlike their Western counterparts, the Tarahumara don’t replenish their bodies with electrolyte-rich sports drinks. They don’t rebuild between workouts with protein bars; in fact, they barely eat any protein at all.

How come they’re not crippled? I’ve watched them climb sheer cliffs with no visible support on nothing more than an hour’s sleep and a stomach full of pinto beans.

Shouldn’t we, the ones with the state-of-the-art running shoes and orthotics, have zero casualty rate and the Tarahumara, who run far more, on far rockier terrain, in shoes that barely qualify as shoes, be constantly hospitalised?

The answer, I discovered, will make for unpalatable reading for the $US20 billion ($A2.5b) trainer-manufacturing industry. It could also change runners’ lives forever. Dr Daniel Lieberman, professor of biological anthropology at Harvard University, has been studying the growing injury crisis in the developed world for some time and has come to a startling conclusion: “A lot of foot and knee injuries are caused by people running with shoes that actually make our feet weak. Until 1972, when the athletic shoe was invented, people ran in very thin-soled shoes, had strong feet and had a much lower incidence of knee injuries.”

Lieberman also believes that if modern trainers never existed, more people would be running. And if more people ran, fewer would be suffering from heart disease, hypertension, blocked arteries, diabetes, and most other deadly ailments of the Western world. “If there’s any magic bullet to make human beings healthy, it’s to run.”

The modern running shoe was essentially invented by Nike. The company was foundered in the ‘70’s by Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman. Before these two men got together, the running shoe as we know didn’t exist. Athletes from Jesse Owens, who won four track and field gold medals at the 1936 Olympics, through to Bannister all ran with backs straight, knees bent, feet scratching back under their hips. They had no choice; their only shock absorption can from the compression of their legs.

Bowerman didn’t actually do much running. He only started to jog a little at the age of 50, after spending time in New Zealand with Arthur Lydiard, the father of fitness running.

Bowerman came home a convert, and in 1966 wrote a besting book whose title introduced a new word and obsession to the newly fitness-aware public: Jogging. In between writing and coaching, Bowerman came up with the idea of sticking a hunk of rubber under the heel of his pumps to stop the feet tiring and give them an edge. Bowerman called Nike’s first shoe the Cortez – after the conquistador who plundered the New World for gold and unleashed a horrific smallpox epidemic.

It is an irony not wasted on his detractors. In essence, he had created a market for a product and then created the product itself. “With the Cortez’s cushioning, we were in a monopoly position probably into the Olympic year, 1972,” Knight said. The company’s annual turnover is now in excess of $US17 billion and Nike sells its products in more than 160 countries.

Since then, running shoe companies have had more than 30 years to perfect their hi-tech designs so, logically, the injury rate must be in free fall by now. After all, Adidas has come up with a $250 shoe with a microprocessor in the sole that instantly adjusts cushioning for every stride. Asics spent $US3 million abd eight years to invent the Kinsei, a shoe that boasts “multi-angled forever gel pods” and a “midfoot thrust enhancer”. Each season brings an expensive new purchase for the average runner.

No manufacturer has ever invented a shoe that is any help at all in injury prevention. If anything, the injury rates have actually crept up since the ‘70s – Achilles tendon blowouts have seen a 10 per cent increase.

Last year, Dr Craig Richards, a researcher at the University of Newcastle in NSW, revealed there were no evidence-based studies that demonstrated running shoes made you less prone to injury. Richards was so stunned that a $25 billion industry seemed to be based on nothing but empty promises and wishful thinking that he issued the following challenge: “Is any running-shoe company prepared to claim that wearing their distance running shoes will decrease your risk of suffering musculoskeletal running injuries?”

What are the benefits of all those microchips, thrust enhances, air cushions, torsion devices and roll bars? The answer is still a mystery.

“Paying several hundred dollars for the latest in high-tech running shoes is no guarantee that you’ll avoid any of these injuries and can even guarantee that you will suffer from them in one form or another. Shoes that let your foot function like you’re barefoot – they’re the shoes for me.”

Soon after those two Nike sales reps reported back from Stanford, the company’s marketing team set to work to see if it could make money from the lessons it had learned. Nike Sport Research Lab, assembled 20 runners on a grassy field and filmed them running barefoot. When he zoomed in on their feet, he was startled by what was happening. Instead of each foot clomping down heel-first as it would in a hi-tech shoe, it behaved like an animal with a mind of its own – stretching, grasping, seeking the ground with splayed toes, gliding in for a landing like a lake-bound swan. “That make us start thinking that when you put a shoe on, it starts to take over some of the control.”

“We found pockets of people all over the globe who are still running barefoot, and what you find is that, during propulsion and landing, they have far more range of motion in the foot and engage more of the toe.”

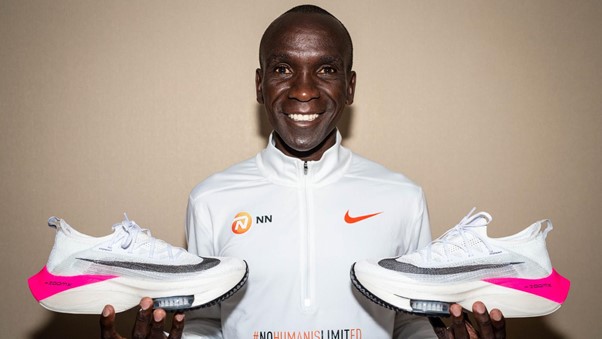

Nik’e response was to find a way to make money out of a naked foot. It took two years of development before Pisciotta was ready to unveil his masterpiece. It was presented in TV ads that showed Kenyan runners padding along dirt trail, swimmers curling their toes around a starting block, gymnasts, Brazilian capoeira dancers, rock climbers, wrestlers, karate masters and beach soccer players. And then comes the grand finale: we cut back to the Kenyans, whose bare feet are now sporting some kind of thin shoe. It’s the new Nike Free, a shoe thinner than the old Cortez dreamt up by Bill Bowerman back in the ‘70s. And Nike’s slogan for this breakthrough shoe? “Run Barefoot”.

The cost of this return to nature? A conservative $140 to $160. But, unlike the real thing, experts may still advise you change them every three months.

If you enjoyed this article you may also enjoy reading Endurance Training Jargon, or Gordon Pirie’s Laws Of Running.